Megan Phelps-Roper, the granddaughter of fundamentalist preacher Fred Phelps of the Westboro Baptist Church in …

Megan Phelps-Roper, the granddaughter of fundamentalist preacher Fred Phelps of the Westboro Baptist Church in …

When Megan Phelps-Roper—heir apparent to the notorious Westboro Baptist Church founded by her grandfather Fred Phelps—left with her younger sister Grace in November, they joined that rare population of women who leave extreme faiths.

Indeed, more women are more likely to be cast out—like former WBC follower Lauren Drain, whose memoir comes out this week. Experts say to an extreme faith — be they cults or fringe elements — there is only us vs. them, chosen vs. unenlightened, saved vs. sinners. To leave is to forgo community, structure, kin and perhaps one’s eternal soul. Leaving meant “sadness, and Hell, and destruction, and losing the only family, friends, faith, truth I’d ever known,” Phelps-Roper recently wrote. “It simply wasn’t on the table.”

WBC spokesperson Steve Drain characterized the Phelps-Roper sisters’ departure as “the natural course of things” to Topeka Capital-Journal, adding, “They wanted to serve themselves.” (Drain is the father of Lauren Drain.) He also said:

Those two girls were kind of straddling the idea that they wanted to be of the world but that they would also miss their family, the only thing they ever knew. If they continue with the position that they have, those two girls, yeah, they’re going to hell. (Feb. 7, Kansas City Star)

That kind of pronouncement can cement a follower or make an apostate. “It is so so rare when any of them leave,” explains Andrea Moore-Emmett, who wrote “God’s Brothel: The Extortion of Sex for Salvation in Contemporary Mormon and Christian Fundamentalist Polygamy,” to Yahoo!. “In many cases, some of these individuals are pushed to such extremes. Somewhere inside them, they just say enough is enough.”

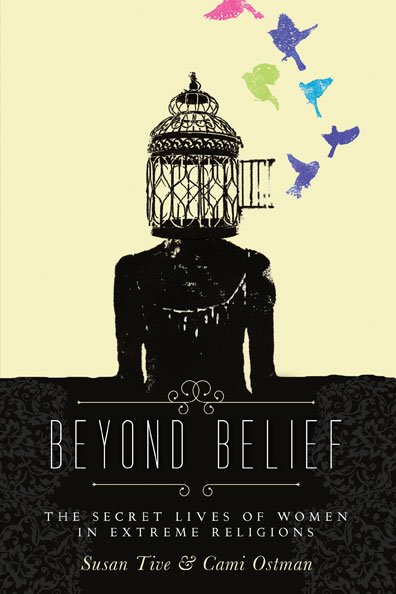

They come to that wrenching moment after feeling something is unjust and arbitrary: Beliefs dictate one way of living, yet they witness daily inconsistencies, even blatant contradictions, in how peers or leaders behave. “There does seem to be a realization that they’re being kept smaller than they could be,” Cami Ostman, co-author of the upcoming anthology “Beyond Belief: The Secret Lives of Women in Extreme Religions” tells Yahoo!. “There’s a betrayal in the community, maybe it’s a betrayal in the belief system … and the explanation that’s given doesn’t size up.”

Women raised in restricted sects can be “pounded down,” says Moore-Emmett. “It’s beyond even what we see in a domestic violence shelter.” Yet even these women—raised to be submissive, even sexual servants, to men—find their faith shaken when daughters follow the same path, she adds. In extreme polygamy cases, their girls may even be traded with other groups, across state lines.

“They just have some resiliency that is just beyond what you would imagine—what they could ever imagine—that they have in themselves,” Moore-Emmett says. “They find it in themselves to start questioning, to start finding that there might be another way to live.”

Community and control

Defections are also rare because such closed faiths provide a sense of community for women and fulfill women’s relational goals, says Patricia Millar, who studied cultic groups. “They felt a strong sense of belonging and mattering, more important than themselves, like a spiritual transcendence goal,” she tells Yahoo!. In her research of 22 people who left cults (mostly women), they had been deeply committed and often experienced a “gung-ho period,” usually during adolescence. “They’re almost more vehement. The group capitalizes on that, puts them in positions so that they can do things for the group. Those investments are golden handcuffs, if you will.”

Beyond Belief – addresses what happens when women of extreme …

Reinforcement comes from the leadership and peer level. Ostman, who grew up a Pentecostal evangelical fundamentalist in Washington, says those who didn’t attend church were deemed to be “backsliding.” Fellow worshippers were encouraged to reach out to “heap burning coals”—not as searing as it sounds. “You would be extra, extra nice to them so they felt guilty,” she recalls. Doubts are dismissed by diminishing any suffering, comparing it to what their prophets endured. Followers—male or female—can also be undereducated, making independent survival in 21st-century America seemingly insurmountable.

According to Millar, the tradeoff for security is invariably control over female sexual behavior: who they marry, why they won’t marry at all, what clothes they wear—down to underwear. In some extreme LDS groups, older men compete for the female resources, and experts say teen boys and young men can be kicked out of the group and their wives reassigned. (Tim Phelps, uncle to the departed granddaughters, wrote in blog comments: “Here is the accurate view of these two ladies who in fact left for … hold your applause … you’ll be surprised (NOT) … sex.”

Millar knows about sexual exploitation firsthand. She went from being a straight-A high school graduate headed to university to joining an “alternative community” at age 17. (Millar has requested the group be kept anonymous.) On its face, the group emphasized living intentionally with a commitment to enhanced sensuality. “Orgasm is a powerful form of conditioning. You’re flooding your body with endorphins,” Millar says. “Additionally, psychoactive drugs such as marijuana and LSD were in frequent use.”

The highs kept people addicted to the lifestyle. Teenage girls, herself included, were manipulated into relationships with older men. At times, she was the victim of intimate partner violence. Females who bore children were expected to raise them communally in conditions that resulted in neglect and, for some, sexual abuse. Millar stayed nearly eight years, despite witnessing the deterioration of key leaders from drug use, including heroin. “I finally left when I had a 6-week-old baby,” she tells Yahoo!.

Surviving faith

For such an uncommon group, many have been speaking out. The anthology “Beyond Belief,” due out in April, relates first-person accounts from a range of women—former Mormons, Muslims, Jehovah Witnesses, Seventh-day Adventists. Nate Phelps, estranged son of Fred Phelps, condemned the WBC threat to picket the Newtown, Conn., victims’ funerals. Another WBC granddaughter, Libby Phelps Alvarez, who left the group in 2009, told the “Today Show” about how her family prayed for people to die. Her cousins Megan and Grace Phelps-Roper, who carried the message of hate preached at funerals and public events to Twitter, now use that as conciliatory outreach. Megan also wrote in a February open letter:

We know that we’ve done and said things that hurt people. Inflicting pain on others wasn’t the goal, but it was one of the outcomes. We wish it weren’t so, and regret that hurt. … We know that we can’t undo our whole lives. We can’t even say we’d want to if we could; we are who we are because of all the experiences that brought us to this point. What we can do is try to find a better way to live from here on. That’s our focus. (Turning Points.)

Whether you were born into it or came to it later in life, breaking faith and dismantling community ties can be traumatic. “The fallout and repercussions are very scary and very overwhelming,” says “Beyond Belief” co-author Susan Tive. Among Jehovah Witnesses, “you’re what they call ‘disfellowshipped.’ Even their parents in some cases aren’t allowed to speak to them anymore.” Their names are announced before the congregation, to be shunned. For some Orthodox Jews who marry outside the faith, they are considered dead.

“It’s very bittersweet,” she adds. “There are relationships you let go, that you will lose forever. It’s a vacuum. You lose God in some ways.”

Moore-Emmett says someone on the outside has to be there to help, especially for those who have been shut away from society, raised in an us-versus-them paradigm. “It’s very difficult to make a new life when you don’t have any job skills, when your education is very limited, you don’t have any family,” she says. Besides experiencing culture shock, apostates can live in fear that the leaders will reach out and strike them dead and, for years, they constantly question their own thinking.

Yet for those who get out, it’s worth their salvation, Moore-Emmett says. “One women said to me, ‘If I’m going to hell, then I’d rather go to hell.'”