Retiring a slogan (Justin Sullivan:Getty Images)

Stand Your Ground. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Show Your Papers (Please).

Reducing a complex concept into a slogan is an uncertain art, but one that people have tinkered with for centuries. The word “slogan” itself hails from the Gaelic sluagh-ghairm—a battle cry, one that the Scottish Highlanders whooped as they stormed into the fray, how a liege would declare his allegiance to his lord, and, in the United States, most memorialized in that call to arms “Remember the Alamo.”

These days, instead of military chiefs, the consultants and companies do their “Mad Men” mojo on complex laws and political concepts, with the media perpetuating slogan shorthand to explain legal defense in the Trayvon Martin case, a military policy’s postmortem at the Pentagon’s first gay pride celebration, and the Supreme Court’s ruling on Arizona. And in case you couldn’t keep up before, our meme-obsessed flightiness has sped up the slogan life cycle, which in turn increases the demand for more.

Are we sheep for falling for bumper-sticker politics? Might this an inevitable—and even time-honored—approach to sift out arcane matters for a demanding citizenry? How does sloganeering work, and does it?

From alliteration to freedom: Political campaign slogans go back at least to the 1800s, when “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” made a catchy tune for Whig Party candidate William Henry Harrison (a hero in the 1812 Battle of Tippecanoe) and veep John Tyler—catchy enough for Harrison to beat President Martin Van Buren to become No. 9. A couple of centuries later, Barack Obama borrowed the United Farm Workers cry, “Yes We Can,” for his 2008 campaign.

Reducing policies to slogans may be a tad more challenging, but that, too, has a long history. In 1844, senator William Allen boiled down a border territory dispute between the United States and the U.K., which controlled British Canada, to “Fifty-four/Forty or Fight!”; President James Polk later adopted the slogan. “Alliteration took the place of any reflection,” says Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist and a frequent contributor to NPR’s “Fresh Air.” (Polk later compromised and set the boundary at 49 degrees north.)

Supreme Court

Modern-day slogans of individual rights and freedom: Poetic repetition has given way to more outright repetition (“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”), patriotic appeals, life-or-death dichotomies, and just plain toughness. “Stand Your Ground,” for instance, “projects manliness, independence, and courage,” points out UC Berkeley linguist Robin Lakoff. Compare that with George W. Bush’s phrase “Cut and Run,” which implied that naysayers to the Iraqi conflict were cowards with no backbone. A stand, on the other hand, means “I’m not going give up an inch,” Lakoff explains. The phrase also hedges on “the notion of rights—’I have a right to stand my ground; it’s very hard to counter.” Even the word “ground” has a ring of Manifest Destiny, the 19th-century American notion of an almost divine decree to expand westward and set up homesteads.

The Supreme Court’s Arizona ruling focused critics and proponents alike on “Show Your Papers Please” (or just plain “Papers Please”), which allows police to ask for proof of citizenship. While straightforward, the slogan could conjure up the days of Nazi Germany or Communist China, when identity papers symbolized a citizenry helpless against tyranny. It also could resonate in a crabby anti-big-government climate, with its stifling rules. “Bureaucracy is what we hate, because it’s complicated,” Lakoff says. “Notice how many of these phrases are good ol’ English Saxon. We hate the Latin or Greek—like the word ‘bureaucracy.'”

Death Tax (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Death Tax (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Mass mind control or reinforcing the party?: The belief that words can change minds goes back to George Orwell, whose fiction introduced the idea of group-think. Orwell aside, is being swayed by a slogan a dereliction in citizen duties, or is it the reality of too many competing ideas? “The idea of the informed electorate—it’s not going to happen. [Most] people don’t have the time and interest,” Nunberg says, quoting pioneering journalist Walter Lippman, “The facts far exceed our curiosity.”

To penetrate, an emotional appeal is essential, says research scientist and Syntience robopsychologist Andrea Kuszewski. “The more someone is personally and emotionally invested in an idea, the more it will resonate with them, and the more likely they are to adopt it as a belief.” An effective slogan doesn’t just sum up an idea in two bullet points but makes it easy for people to use that slogan as a cheat sheet when they talk about the issues with others.

Often, however, slogans merely end up reinforcing a group’s beliefs. “You drum up the emotional impact and give them a solid ‘take-home point’ that they can use to identify with the other members of the group.”

The limits of “Mad Men” politics: In 1984, Democratic presidential candidate Walter Mondale evoked the little old lady from Wendy’s and demanded of rival Gary Hart’s platforms, “Where’s the Beef?” Borrowing from advertising, Nunberg tells Yahoo!, means one less focus group for politicians. “The work has been done for them in a series of 30-second commercials.”

Then again, he cautions, “People make more of a fuss about these things then they ought to.” In the “Right to Die” controversy, when asked if they supported physician-assisted suicide versus helping patients end their lives, people shifted 15% in favor when the word “suicide” was omitted. On the other hand, spinning estate tax as death tax barely shifted opinion either way on the topic.

Another way to say Stand Your Ground?

Another way to say Stand Your Ground?

Democrats vs. Republican: Not all slogans are controversial: “Stand Your Ground” has competing phrases like “Make My Day” and “Right to Kill,” but “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” pretty much described the 1993 military policy. Whatever the political spin, progressives and conservatives might agree on thing—conservatives are much better at verbal shape-shifting. GOP pollster Frank Luntz has famously built a career on phrase makeovers: oil drilling to energy exploration, global warming to climate change, estate tax to death taxes, and his 2009 memo on fighting health-care reform. His consulting website points out an increasingly judgmental electorate:

We have become a hyper-attentive nation that is quick to judge. The words and visuals you use are more important than ever in determining whether you win or lose at the ballot box, the checkout line, and the court of public opinion…. Remember: “It’s not what you say. It’s what people hear.” (Luntz Global)

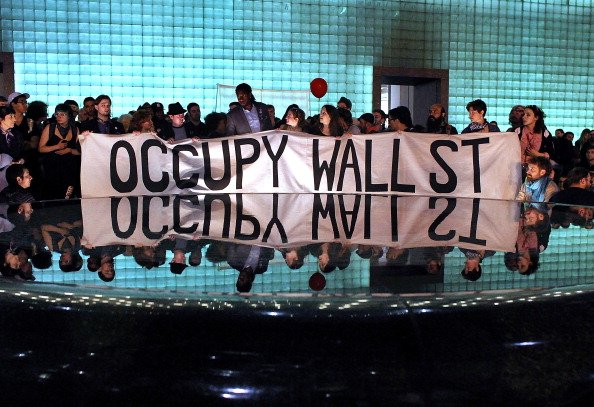

Occupy Wall Street is one of those rare successes, an assertive phrase with militant (or call-to-action) overtones declaring war with a perceived enemy. Usually, however, Lakoff says, conservatives know how to appeal to emotion in unambiguous language. “A liberal trying to make up ‘Stand Your Ground,’ it would come out: ‘Maybe if it’s not too much trouble, if you have to do something, but if you had a gun—I mean, but you really shouldn’t have a gun…'” Continued on next bumper sticker.

Occupy Wall Street (Spencer Platt:Getty Images)