Drink up?

Trading lunch boxes isn’t what it used to be.

Overall, about 15 million Americans lay claim to food allergies (as opposed to food intolerances, but more on that later). One out of 13 children may be susceptible. Some allergies can trigger anaphylaxis, when your body goes into immune overload shock. Whether allergens are a peanut, a glass of eggnog, a pat of butter, or a dish of honey walnut prawns, these days more people seem to be rejecting them.

Food allergies (or at least, our ability to diagnose them) are on the rise. But why?

Short answer: Scientists aren’t sure, and they’re just beginning to dig into the complex world of the human gut, the bacteria within, and the importance of understanding not only what goes down our gullet, but also how much and when.

Food allergies vs. food reactions/intolerances: There’s a big difference between food allergies and food intolerances, Dr. Stephanie Leonard of the U.C. San Diego School of Medicine said to Yahoo!. Reactions can be immunologic (food allergies) or non-immunologic. The latter can be pharmacologic (chemical-triggered), toxic (food poisoning), or metabolic.

“The term [allergy] is kind of misleading; you think of sneezing, coughing. ‘If my kid has a reaction to any food, they must have a food allergy,'” says Dr. Ruchi Gupta, lead author of the new study “Geographic Variability of Childhood Food Allergy in the United States.” She tells Yahoo!, “A food allergy can be immune-mediated. Symptoms can be dangerous and even lead to death.”

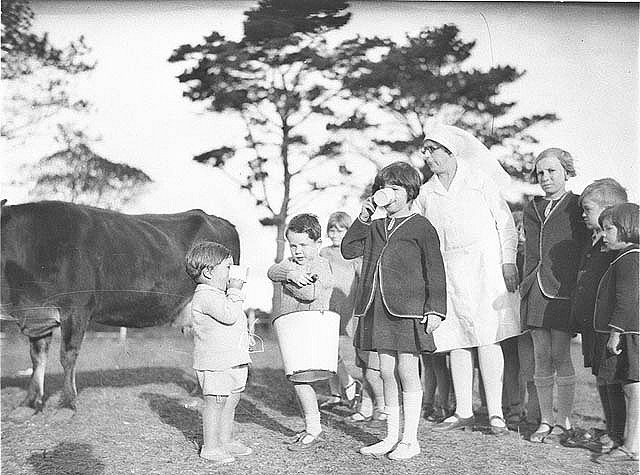

May contain dairy (Scott Olson:Getty Images)

Why the rise in food allergies: Emergency room visits for food allergies reportedly tripled between 1993 and 2006. Other studies note an 18% increase in overall reporting between 1997 and 2007. Is it the population diversity? Pollutants floating in our environment? More foodstuffs introduced into our cuisine? All that deliciously bad stuff we eat? Might a kind of persuasion bias be affecting appetites — you know, urban Nervous Nellies who latch onto a health cause like a fashion trend?

While the public uses the terms “food reactions” and “food allergies” interchangeably (stop that please, see above), “researchers do believe that the prevalence of true food allergy is increasing, because such findings have been replicated in multiple studies using different populations,” Leonard says. “This rise seems to be specific to developed countries.”

Gupta’s recent study found living in a city upped your odds of having allergies. Other research suggests more possibly susceptible groups:

Racial and ethnic differences have not been explored widely. In telephone surveys, shellfish allergy was reported at a significantly higher rate among black/African American subjects than white subjects. … Boys appear to be at higher risk than girls, and perhaps women more than men. … One study showed a higher risk for increased affluence. Obesity may be … associated with increased risk for food allergy as well. … Delaying exposure to allergenic foods in infancy and early childhood may be a risk factor for food allergy. (“Epidemiology of food allergy,” 2011, the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology)

Healthier farm living? (Cancan Chu/Getty images)

The hygiene hypothesis: There may be as many theories as food allergies about their prevalence, including from when we start eating certain foods, vitamin D levels, fatty acids intake, how we process food, and even antacid use.

One beguiling theory is the hygiene hypothesis. “We live in a clean environment, and our immune system is not busy fighting off infections or parasites. So instead it overreacts to harmless things like food,” Leonard says. “This is supported by the fact we don’t see high rates of food allergy in developing countries.”

That might account for the differences in American city and country dwellers. “Children in rural environments, particularly kids who grow up on farms, seem to have less,” Gupta says. The nuances could be attributed to locally grown vs. processed food or hanging around animals. For instance, kids with pets have a lower chance of having asthma, and there’s a lot of overlap between asthma conditions and food allergies.

Balancing what’s in our gut: Most of us have heard about the Human Genome Project’s DNA mapping, but only recently have we heard about the Human Microbiome Project. The five-year microbe census reveals that a trillion bugs reside in our guts alone, and everyone’s gut carries a different population — though they all do the same tasks.

In our hand-sanitizing age of plenty, modern diet and medicines tinker with that balance, leaving our delicate innards vulnerable to a host of ills. The founder of Human Food Project, in a recent tribute to farmers’ markets, recommended a return to natural foods to toughen us up.

Increasing evidence suggests that the alarming rise in allergic and autoimmune disorders during the past few decades is at least partly attributable to our lack of exposure to microorganisms that once covered our food and us. … This research suggests that reintroducing some of the organisms from the mud and water of our natural world would help avoid an overreaction of an otherwise healthy immune response that results in such chronic diseases as Type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, and a host of allergic disorders. (June 20, the New York Times)

Food allergies, not just for kids: The good news is, you can outgrow food allergies — many kids grow out of milk allergies. The bad news is, you can also develop them later in life. And, like a bee sting, allergy reactions can worsen. “Food allergies are unpredictable. Even if you’ve only had a mild reaction in the past, your next reaction could be severe, and vice versa,” Food Allergy Initiative (FAI) executive editor Mary Jane Marchisotto tells Yahoo!. She recommends going to a qualified allergist or immunologist for testing.

One good thing about increased awareness: People are doing the right things, like the probiotic yogurt craze. The obesity campaign may indirectly benefit food allergy sufferers, as fast-food menu makeovers and soda bans contribute to a healthier system overall. And, while food allergy research didn’t have the kind of funding that, say, asthma did, more investigators are now tackling the subject. Funders such as the FAI hope not just for a treatment, but also a vaccine. How we interact with our food is complicated, Gupta says. “It’s hard to tease out, but not impossible.”