When we’re all paying for things with smartphones, what’s going to happen to the tip jar? How will people drop change (or more) to thank counter workers?

In the United States, about 31 service professions include — and depend upon — tipping. If Apple Pay gets people to flash phones instead of cash, shoppers might not be the only ones walking around without cash in their pockets.

Then again, mobile payments could clear away the confusing social rules that surround tipping, standardize the practice, and maybe even get wage-earners to a place where they don’t have to depend on the arbitrary kindness of strangers.

So which is it? It’s both.

Your change is coming

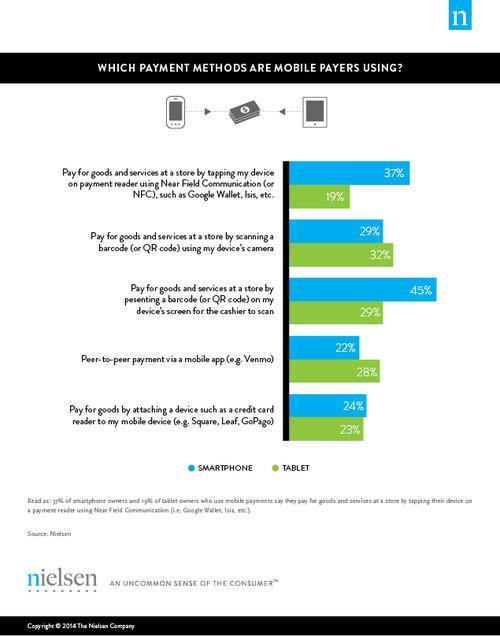

Credit and debit cards have been curtailing our cash habit for a while. A recent Bankrate survey found that 40 percent of people were carrying around less than a sawbuck. Turns out there’s an upside: People tend to spend more with credit cards than cash, and that bleeds over into tipping.

“Globally, cash is in a defensive position,” says Magnus Thor Torfason, an assistant professor at the University of Iceland School of Business who also co-founded the UK-based mobile payment system HandPoint. Still, he says, “People in the U.S. have an aversion to not tipping,” which explains why electronic payments haven’t undermined our custom that drastically.

And cash is still king when it comes to rewarding workers like valets, maids, and skycaps. Forrester Research analyst Julie Ask says that while mobile payments have worked out really well for small, cash-based transactions, “the hurdle is high here for tips,” she tells Yahoo. “If I pay with my phone, I am not going to dig into my purse to get change for a tip.”

In one traditionally cash-based business, taxis, companies have been experimenting with methods to keep the tips coming in as their industry shifts to electronic payment. In a 2013 study called “Default Tips,” cabs equipped with digital payment screens recommended at times two different tipping calculations. Sure enough, riders in the cabs suggesting higher rates paid up more, although there was some backlash: Some balked and left nothing.

Companies like Square, OpenTable, and Starbucks have tweaked their algorithms for suggested tips, too. Square led the charge, literally: Initially, the tip option appeared alongside the signature page. Now it appears on its own screen, with options in percentages (15 to 25 percent), dollar amounts (“custom tips”), and no tip. A “smart tip” option that sellers can enable has led sellers to report 35 to 100 percent increases.

It’s been three years since Starbucks launched its mobile app. It initially had no topping option, but the coffee chain launched digital tipping just this past March. “Customers wanted a way to thank their baristas,” a spokesperson told Yahoo Tech. No doubt baristas also appreciate being thanked.

Highway robbery to fair wage

If you think tipping is highway robbery, well, it was, according to some historians: The Medieval practice of tipping highwaymen to avoid being robbed evolved into “giving the vails” — or coins — to servants.

The European practice truly became widespread with the rise of the middle class, and then made its way to America. Today, tipping itself is a $40 billion part of the economy in the United States. That’s remarkable, Torfason points out to Yahoo Tech, considering that tipping tends to be more prevalent in lower-income and also more corrupt countries. He says the United States is a “special outlier when you consider the developed economies.”

But it’s still awkward for us. Lois Hamblet — who founded the Massachusetts-based Ziptip in 2010 — had her “epiphany moment” while shopping for her organic food. “I was staring at my iPhone and thinking, ‘Why can’t I tip anyone from an iPhone?’ ” She wondered why a grocery clerk couldn’t get special recognition for service. “Why do we tip some people and not tip others? Why don’t we tip yoga instructors and grocery store clerks? There’s a lot of low-wage workers out there.”

Ziptip was among the first of a slew of tipping apps trying to make sure that wage earners get their due. Likewise, Mike Cassin said he co-founded TipEasy with his childhood pal after a skiing trip. “Like modern age people, I didn’t have cash on me,” he admitted. He remembers being on the other side of the equation and the frustration of not being tipped.

Tips for everyone?

Americans aren’t just approaching a cashless economy — we’re also in a sharing economy. Uber, for instance, can turn almost anyone with a car into an entrepreneur, but its lack of a tipping option prompted Lutfi Abed to create Tap2Tip. “I do believe that new frictionless mobile wallets will substantially increase and improve on the tipping experience,” Abed says.

The common thread among all these founders: Get those tips straight into the hands of the workers as quickly as possible. That money means much more than a little “extra” for people earning sub-minimum wages (also known as the tipped or cash wage). Seven states still let certain industries pay their staff $2.13 an hour. The rest is supposed to come from tips. These wages usually land tipped workers in the bottom quartile of American workers as far as total pay. And the recent New York City settlement with an airline service contractor shows that they don’t always get their fair share.

As much as opponents want to ban the practice in favor of more equitable wages, Americans are too versed in using their dollars and cents as a way to express gratitude.

Gratuity gratification

But why? Why do we insist on this arcane, perplexing way of compensating people? According to Cornell University professor Michael Lynn, dubbed a scholar of tipping, Americans are motivated by the practical and the psychological: to reward service, buy better service in the future, and help the server out.

Plus the psychological twist: “We purchase social esteem or to avoid losing social approval,” he explains. And this social approval we’re trying to earn isn’t from family or friends, but from the server. We can’t help feeling what Lynn calls an “internal obligation or duty” to the server, even if he’s a complete stranger whom we might never see again.

As mechanized as commerce is becoming, recognizing service is really an intimate human exchange. The TipEasy founders were surprised that some people send tips hours or days after receiving service.

“Tipping is really complicated,” Ziptip’s Hamblet says, “and it’s really emotional.”

Mandatory thanks?

But will that emotional relationship get lost in the digital transition? With cash, “it was basically between you and the waiter or the waitperson, and not between you and the firm providing the goods and services,” Torfason says. With electronic payments, “tipping becomes part of the price, part of the institution, more depersonalized — and that is a change that will continue as mobile and electronic payments become more widespread.”

Tipping could become so standardized that Americans will start doing what Europeans already do — adding a mandatory service charge. That might lead to a fairer distribution of funds but, Torfason predicts, “it will make it more difficult for the employees to hold onto the tips. It will strengthen the hand of the employer and weaken the employee.”

Right now, some tipping apps are trying to do both — work with the establishment but still find a way to slip a little something directly to the servers. That means servers must opt into a database, which some are eager to do (like limo drivers), and others aren’t (like wait staff). And if servers aren’t in the tipping system, then you would either have to persuade them to join up or ask for emails or telephone numbers.

Or you could just slip them some cash.