Photo credit: StockFood / Luzia Ellert

It’s one thing for your brother to hate green vegetables, your beloved to avoid dairy, or your best friend to swear off offerings from the entire country of India.

But good luck cooking for a guest who turns his nose up at mangoes but not pineapples, picks out tomato slices from a burger, and mercilessly plucks at walnuts studding a brownie. It’s like you need a course in Bayesian statistics to figure out his contradictions.

Only, there just might be a pattern that scientists are only beginning to hone in on to explain picky eating: texture.

By now, most people know about the importance of smell (aroma) and the five basic tastes (sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, umami). Texture—or what the aspiring foodie understands as “mouthfeel”—is part of the holy trinity of flavor. Yet that third dimension may be the most under-appreciated and indefinable part of eating.

“We don’t separate texture from the act of eating,” observes Barb Stuckey, author of “Taste: What You’re Missing.” “We think of it as a physical act, as if there were no sensory stimulation.”

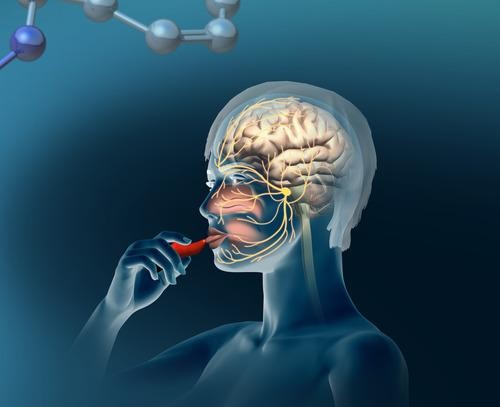

But there’s a whole host of sensory reactions involved even before you sink your teeth in, among them the visual (assessing how crisp that tempura still is) and the aural (the crackle of a salty chip). When the food finally makes its way into your mouth and you break down those cellular walls (also known as chewing), captive flavors get released, which then warm up in your mouth and linger.

As a professional food taster and developer, Stuckey has pushed a lot of prototypes past people’s lips to get their feedback. Even when it comes to “extreme textural aversions, though, many have a hard time pinpointing and articulating what’s objectionable.” Yet while they may not appreciate texture when it’s there, they definitely notice when it’s not. (That’s why those substitute meal shakes, tasty as they may be, don’t quite satisfy.)

“When it comes to texture,” Stuckey said, “we just don’t have a very good vocabulary about that.”

Can’t Quite Put Our Finger On It

So why isn’t texture better understood? There’s actually an international standard, ISO 5492, that defines texture as—wait for it—”the mechanical, geometrical and surface attributes of a product perceptible by means of mechanical, tactile and, where appropriate, visual and auditory receptors.” Talk about a mouthful.

That standard wasn’t even set until 1992. Turns out the modern investigation into texture—or really, sensory research—didn’t start until after World War II. Before then, food researchers considered texture too personal to be measured scientifically. Minds changed, according to the textbook “Food Texture,” after the Army made “considerable investment in developing nutritious rations for its troops, only to find many of them did not appreciate what they were being offered.”

Still, of all the taste elements, texture remains the toughest nut to crack. Capturing that crowd-pleasing mouthfeel has been part of a billion-dollar food industry: Think of the French fry wars or the quixotic attempts at (delicious) nonfat ice cream. “Food companies have invested a lot in science to understand how to manipulate the texture of foods,” Institute of Food Technologists spokesperson Kantha Shelke wrote in an email. “After appearance and taste, it is the texture that brings people back to a food.” Findings, though, often remain hush-hush to maintain the competitive advantage.

Among academics, “there’s kind of a vicious cycle,” says Ivan de Araujo, who was among the first to track the appreciation of texture and taste to the brain’s insular cortex. Scientists preferred mapping out taste buds and olfactory receptors because of the body of work already done in these areas. “You don’t see as many researchers generally interested in texture as you see in taste and olfaction,” he said.

Still, de Araujo thinks that a map of how we experience texture might be available in the next five to 10 years. So just as we’ve embraced the “supertaster,” we might be able to identify—and understand—the “hypertexturalist.”

You Say ‘Tomato,’ I Say ‘No Thanks’

In the meantime, surveys have been able to suss out patterns among picky eaters — and enemy number 1 is the raw tomato. The aggrieved tomato is damned as slimy, wet, and gelatinous. Fundamentally, it may symbolize what picky eaters hate: change.

“When you think about it, it has a lot of textural transition,” explains Dr. Marcia Pelchat, a biopsychologist at the nonprofit Monell Chemical Senses Center. “You have the thin skin that can stick to your soft palate, you got the flesh that can be grainy, and you got the slimy stuff which is bad.” And just as they would turn away from a strawberry because of its nasty achene (those little dark specks), the tomato seeds get picky texturalists gagging. Picky eaters don’t want itsy-bitsy bits of nonsense interrupting a smooth eating experience.

Of course, that same “textural differential” — as Stuckey calls it —can be a food lover’s lustiest ambition. Unlike the picky eater who would never mix mashed potatoes with lumpy peas, an adventuresome eater can get giddy over the caviar-flavored gels that pop in the mouth like candy. Mixing textures isn’t just restricted to five-star dining experiences. In the junk food universe, the Oreo embodies a zenith of chocolatey crunch and the soft, yielding cream of sugars and shortening. “The ultimate in culinary nirvana,” Stuckey says, “is contrast.”

Spice and Everything Nice

Another point of contention among fussy texturalists: spiciness. Yes, spiciness is actually a texture. Remember ISO 5492, which included “tactile” in its definition? Touch in this case comes from the fibers surrounding your tastebuds, which belong to the trigeminal nerve—the same one that tells you something is hurting. Hot sauce, or a carbonated soda for that matter, will stimulate those open nerve endings.

“Our response to spiciness is a pain response,” Stuckey explains. That’s why many of those so-called hyper-tasters—people who pack a lot of papillae on their tongue—don’t care for the hot stuff, as the stimuli can be overwhelming.

Texturalists on both sides of the spectrum may agree on one thing: the exquisite perfection of chocolate. “One of the most seductive qualities of good chocolate is that it melts precisely at human body temperature,” Stuckey writes in her book, “which provides a textural experience unlike any other food.”

Spoiled Rotten?

Could picky texturalists have pronounced survival instincts? Truly slimy foods, after all, indicate spoilage.

There are studies suggesting that some food neophobia—the fear of trying new foods—might be genetically determined. Then again, studies also show even the most fastidious nibblers can get over their aversions through repeated exposure.

And even entire societies can change textural tastes: One 2000 paper claimed the “explosion of Oriental foods and restaurants” taught Americans to “consume firm, crisp cooked vegetables which in the past were expected to be soft and almost mushy.”

“Eastern, especially, Chinese and Japanese cultures have a more diverse vocabulary than Westerners to describe and appreciate different textures,” Shelke agrees. They “take immense pleasure in eating fiddly, complicated foods”—to the point of soaking all the flavor out of something like sea cucumber just to appreciate its slippery cartiliginous texture.

“Globalization,” she points out, “can open up the repertoire of textures.” With the ability to have the world on a plate whether through restaurants or frozen foods, younger Americans may find themselves craving the rubbery, pasty, gooey—even a raw tomato.

Something, definitely, to chew on.